Where is Vinland? Who shot JR? Few mysteries have captured North Americans’ collective attention and imagination trying to understand what happened to Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated expedition to complete the Northwest Passage. However, a few key breakthroughs have helped us get closer to the truth – most notably, the discovery of Franklin’s two lost ships almost 10 years ago.

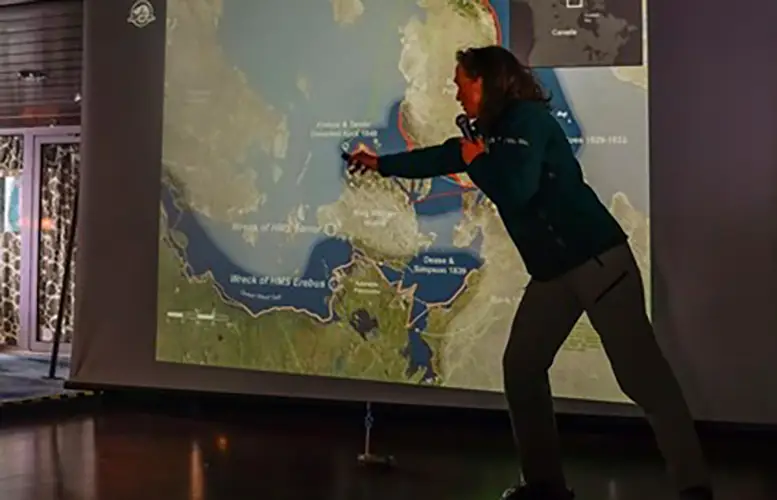

On September 2, 2014, as research vessels methodically combed the island-dotted Canadian Arctic, a blip on a sonar map some distance South of Qikiqtaq (King William Island) caught the eye of underwater archaeologists. They had found HMS Erebus, the first of the two vessels associated with the expedition to be located since they went missing in April 1848. Parks Canada made the discovery, drawing on Inuit oral tradition relayed by the late Louie Kamookak, illustrious historian and educator, and this September marks the 10th anniversary since the ship was located, but many questions remain.

Why did the expedition end up trapped in the ice for over two years? What prompted the men to abandon the two ships? Are the shipwrecks located far from where they were abandoned? Was Sir John Franklin buried at sea or on land? The best way to get closer to the truth is by joining Adventure Canada this year on one of their Northwest Passage Itineraries through interpretation from subject matter experts and guides.

“This year will be an exciting one to travel with Adventure Canada to these areas,” says Ken McGoogan, Franklin Expedition expert, award-winning and bestselling Canadian author, and long-time Expedition Team Member with Adventure Canada. “With the discovery of new artifacts, new information, and even ground-breaking DNA evidence identifying the remains of some of the expedition party, we are getting closer than ever to know what really happened. On these journeys, we will not only talk about the events of the expedition on board but also visit the gravesites on Beechey Island where Franklin buried the first three sailors who died during his expedition.” McGoogan is set to join the Into the Northwest Passage sailing this year as an expedition team member.

On Into the Northwest Passage and Out of The Northwest Passage this summer, explore the Franklin Expedition through onboard programming and education. Sail alongside renowned regional experts, scholars, locals, explorers, and authors, learning through onboard presentations, panels, films, and debates about the famous expedition.

HMS Erebus was built by the British Royal Navy at Pembroke Dockyard, Wales in 1826. After completing several Antarctic explorations in the early 1840s, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror set sail in 1845 for what they hoped would be an expedition completing the Northwest Passage. This sea route would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The expedition set out under the command of British Naval Officer Sir John Franklin. Of course, we now know this expedition was ill-fated with all 129 crew members perishing mysteriously in what is today called Nunavut, specifically near Qikiqtaq (known in English as King William Island). The last definite information is that both ships were abandoned on April 22, 1848, having been stuck in heavy sea ice since September 12, 1846.

After two years without communication from the expedition party and spurred on by Lady Jane Franklin, widow of Sir John, the Royal Navy sent search parties to look for the ships and their crew – over 39 separate expeditions. Although they found remnants and clues, neither the vessels nor the men were found, and eventually, they gave up hope of ever finding out what happened. At the same time, Arctic locals found peculiar evidence of the expedition, including scattered artifacts, like cutlery, on far-flung shores, and there are even Inuit oral stories telling us that hunters boarded at least one of the ships after it was abandoned and before it sank.

After many failed attempts to locate the lost vessels and discover what had happened to the men of the expedition, Parks Canada, together with partners, launched a new initiative to find them in 2008. It wasn’t until 2014, though, when the research team discovered a clue in the form of a wooden davit on a nearby shore, that it finally hit a breakthrough. Within days of discovering the davit, a sonar image of HMS Erebus was finally captured, ending the almost 200-year search. “I would liken it to winning the Stanley Cup,” said Ryan Harris, Parks Canada Senior Archaeologist, in a short video produced by Parks Canada documenting the discovery.

So, what happened to the doomed expedition over 175 years ago? Various theories have been put forward. But the discoveries of the vessels and the diligent work and insights from researchers like the late Louie Kamookak and others are leading us closer than ever before. Ken McGoogan recently published a sixth book about Arctic exploration. In Searching for Franklin: New Answers to the Great Arctic Mystery, he presents a new theory about what went wrong, arguing that the root cause of the disaster was not lead poisoning or botulism but trichinosis, the result of eating uncooked polar bear meat.