Explore a golden age of architecture from when Japan built the foundation for its modern-day society.

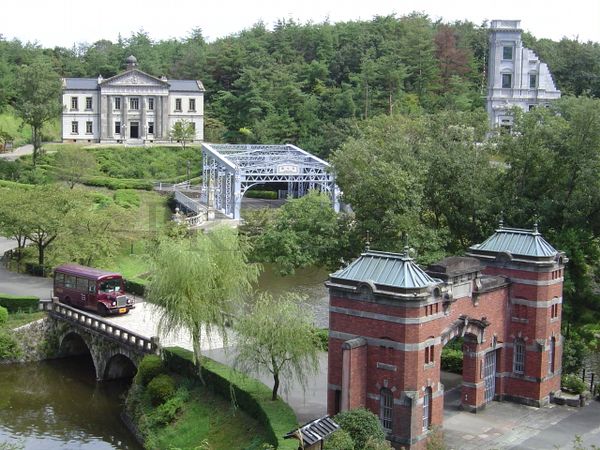

A 40-minute car or train ride north from Nagoya in the heart of Japan’s central Tokai region brings the traveler to Inuyama, a city that boasts not only the sixteenth-century Inuyama Castle, a National Treasure perched on a hill above the Kiso River, but also Meiji-mura, a vast open-air museum and amusement park where iconic architecture of the Meiji period (1868–1912) is preserved on a scenic campus overlooking Lake Iruka.

While the two sites are just 20 minutes apart by car, Meiji-mura is 250 acres in size, worthy of an entire day to see and enjoy in full.

The sole remaining watchtower of Inuyama Castle, dating back to 1537, is one of just a dozen castle structures in Japan that remain in their original form today. Make the most of your time in Inuyama by staying overnight to enjoy these two historical views of Japan: one feudal, the other representing the dawn of the modern age.

Meiji-mura houses approximately 70 original buildings and structures collected from around Japan that are representative of the late-eighteenth to early twentieth centuries, a time when the country opened its doors to the outside world after two centuries of isolationist foreign policy. New materials, styles, and construction techniques were adopted as Japan geared up its industry for modern times. Dating from as early as 1870 to as late as 1927, the structures on display include bridges, vehicles, lighthouses and streetlamps in addition to buildings of all kinds: homes, shops, barracks, factories, banks, schools, clinics, churches, and more. Visitors can tour the buildings both inside and out, ride streetcars that operated in Kyoto in 1910, and board passenger cars from 1908 and 1912 that are pulled by one of the oldest steam locomotives in Japan, the No. 12 that ran between Tokyo and Yokohama in 1874. Eleven buildings and two machines on display are nationally designated Important Cultural Properties, and 21 items have been named heritage works within the history of Japan’s industrial modernization.

Western visitors to the park will find more than a few connections with their own homelands. Meiji was a time when American, French, British, and German architects were commissioned for their versatility in working with stone, brick, and glass. Overseas engineers, too, were hired to supervise the installation and use of imported heavy machinery. St. John’s Church (1907), which formerly stood in Kyoto, was designed with Gothic detailing by an American missionary architect; the Shinagawa Lighthouse (1870) and elegant reception hall of the home of Marquis Tsugumichi Saigo (1880) are the work of Frenchmen. All three are Important Cultural Properties. The Rokugo River Iron Railway Bridge (1877), Japan’s first double-track railway span, was designed by a British engineer and manufactured by an ironworks in Liverpool. Representative of late Meiji, the art nouveau Shin-Ohashi Bridge (1912) that once spanned Tokyo’s Sumida River was designed by domestic engineers using steel members manufactured in the United States. Both have been named heritage works by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

German ingenuity is on display in the water turbine generator that brought electricity to Yamagata Prefecture, and the fully automated early twentieth-century knitting machine that fashioned socks perfectly fitted to the natural curvature of the feet. These can be seen in the Machinery Pavilion, an 1872 structure that formerly served as the Shimbashi Factory of the Japan National Railway and now houses a fascinating collection of such industrial machines. Surprising relics of ingenuity to our present-day eyes, these inventions marked the transition from technologies driven by human, horse, and oxen power to the mechanical energy of turbines, steam engines, and electricity. In this one building it is possible to imagine firsthand how woodblock printing technologies gave way to lithography and letterpress, electric light came to ordinary homes, textiles came into mass production, tunnels were dug, and the first railways were built.

At first these machines were imported from abroad, but gradually came to be manufactured in Japan. The shift to domestic production of them and their precision parts spurred the modernization of transport, too, as steamships, trains, and iron bridges became increasingly feasible. Powered machine tools were used to make the tracks and passenger cars of the first railway, which was launched in 1872, and Western lighthouses were built across the country to ensure safety in a time of increasing maritime traffic.

Edifices that speak to Japanese tastes in design are on display at Meiji-mura as well. Among them are a traditional neighborhood bathhouse, a two-story playhouse for Kabuki and other performative arts, a sake brewery, the home where Natsume Soseki (1867–1916) penned his celebrated satirical novel I Am a Cat, and the summer house of Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904), to name just a few. Also of note are the many buildings that reveal hybrid tastes: Japanese hip-and-gable roofs incorporated, for example, in otherwise Western design vocabularies. One of the most celebrated properties at Meiji-mura is the main entrance hall and lobby of Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, designed in 1923 by Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959). The intricate Oya tuffstone designs were drawn by Wright and hand-carved by top masons from across Japan, and the building’s interlocking planes were suggestive of traditional Japanese architecture. A café inside, overlooking the historical lobby, makes it possible to timeslip back to the days when luminaries from across the globe were able to experience Japan for the first time.

A favorite of history buffs, railway and architecture enthusiasts, photographers, and those who simply enjoy robust walks in the outdoors, Meiji-mura offers something for families, young couples, and independent travelers of all ages. While the terrain is hilly in places, the walking paths are spacious and well maintained, even where they branch off into pleasant groves of trees. A shuttle bus makes two to three rounds per hour of the park’s northern and southern ends, and restaurants, cafés, and food trucks dot the campus.

The co-founder and first director of Meiji-mura was architect Yoshiro Taniguchi (1904–1979). (If the name sounds familiar, it may be because his son Yoshio (b. 1937), also an architect, won international fame for his 2004 design of the new Museum of Modern Art building in New York.) As a member of the Cultural Properties Specialists Council, the senior Taniguchi was concerned that many Meiji-era buildings of significant artistic and historical value had been lost in World War II and that those that remained were in danger of meeting the wrecking ball. Determined to save them, he called upon his former high-school classmate Motoo Tsuchikawa (1903–1974), then vice-president of the Nagoya Rail Road Company. Together the two men eventually established Meiji-mura in 1965.

One-stop flights from the US West Coast to Chubu Centrair International Airport in Tokoname, Aichi depart from Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle.

At the time of this writing, travel restrictions related to the coronavirus pandemic are still in place for much of the world. When they are lifted, the Aichi Tourism Promotion Office looks forward to welcoming visitors back. Until then we will issue bulletins like this one from time to time, showcasing both online and on-site ways to explore and enjoy Aichi’s many offerings.