When you’re lucky enough to catch a glimpse of sunshine in Scotland, it’s as though the entire country steps outside to relish the rare occasion. The atmosphere feels celebratory, as if nature itself has offered a temporary truce for its residents, who have grown all too accustomed to the overcast. For visitors as well, it’s a stroke of luck that doesn’t go unnoticed. Yet, part of Scotland’s timeless allure is its dark and moody side—the brooding skies, rolling mists, and windswept hills that evoke the medieval charm. It’s a country shaped by the drama of the Atlantic Ocean, with low-pressure systems often delivering rain, wind, and clouds in steady supply. But when we arrived in September, the skies parted, giving us clear, sun-soaked days that transformed the landscape and drew communities out of their usual rhythm.

This rare weather seemed like an invitation to explore a lesser-known corner of Scotland’s nature map—a destination that isn’t just preserving the present but actively working to turn back time, restoring its ecosystems to their former glory. We were taking the long route to get from the major city of Edinburgh on the east coast of Scotland, through the highlands of the country to the west coast to a place called Kilchoan Estate (Kilchoan Melfort Trust) in Argyll, Oban. While this area is known to many for being an adventure destination, especially as you work your way up through the isles or lochs, the KMT is a bit more tucked away, operating differently than the other estates found along this less trodden path.

With its heart set on rewilding and marine conservation, KMT is dedicated to reviving Scotland’s natural heritage through innovative projects that balance ecology with sustainable land and sea management. Their initiatives span from woodland restoration to groundbreaking marine research, including their oyster restoration program, which aims to bring native oysters back to Scotland’s waters. By fostering collaboration between scientists, locals, and visitors, the estate has become a hub for hands-on conservation, blending tradition and innovation to create a lasting impact.

While Oban itself is a magnet for travelers—offering a vibrant blend of attractions and earning its title as the seafood capital of Scotland—we set our sights half an hour south, bound for the quiet village of Kilmelford. The journey took us past iconic whiskey pubs and a local dive shop renowned for introducing adventurers to the wild seas of Oban, but our final destination promised something just as captivating. Following the shoreline of Loch Melfort, we seemed to have left the modern world behind. Cell service vanished, the forests grew thicker, and it felt as though we were stepping into a version of Scotland that time had forgotten.

The estate itself was like something out of a postcard, with its carefully managed grounds blending seamlessly into the surrounding wilderness—with the loch still and tranquil to one side and patches of forest on the other. Our journey through Scotland concluded at this very place dedicated to reviving Scotland’s wild. For KMT, it wasn’t just about aesthetics but rather about purpose—a mission to restore what had been lost over centuries of human impact. Scotland’s wild landscapes have not always looked the way they do today. Centuries ago, this region was a dense temperate rainforest and wetlands, as well as home to thriving marine ecosystems.

But human activity—from intensive farming and sheep grazing to widespread deforestation—has reshaped that environment. By the Victorian era, large-scale land reforms prioritized agricultural and recreational use, leading to the displacement of natural ecosystems. These changes were compounded by industrialization, which brought practices like trawling and dredging to the coasts, further degrading habitats both on land and underwater. That’s why today Scotland is considered one of the most nature-depleted places in the world. Much of its original forest cover has disappeared, replaced by monoculture plantations or barren landscapes. Native oyster beds, once prolific in the surrounding waters, have been overharvested to near extinction. Species like the flapper skate, which were once abundant, are now critically endangered, clinging to survival in the waters around Scotland’s west coast.

With KMT’s projects spanning marine conservation, woodland regeneration, and sustainable land management, they are piecing together the fragments of wild Scotland. While every program tied to the estate’s mission felt important, our focus was on their marine efforts—especially the ambitious oyster restoration project. When you think of Scottish seafood, oysters are high atop that list. We’d sampled a variety of them per local recommendations, only to learn from Marnik Van Cauter, KMT’s Marine Asset Manager that most of these oysters weren’t even native to Scotland at all.

In fact, the oysters commonly served at Scottish restaurants are Pacific oysters—a hardy, fast-growing species originally from Japan that thrives in Scotland’s waters but lacks any historical connection to the region. Introduced for aquaculture, these non-native oysters mature in just a year, making them commercially viable and resilient under varying conditions. Yet, as Marnik explained, while they’re remarkably tough, they’re also unfortunately a poor substitute for the fragile, slow-growing European flat oyster that once thrived here. These native oysters take up to three years to mature, but are critical to Scotland’s marine heritage, serving as natural water filters and keystones for broader biodiversity. The challenge, as KMT is discovering, lies in restoring what was lost while balancing the pressures of modern seafood demand.

Marnik, originally from Belgium, first became intrigued by oysters after attending a talk by a neighbouring community-led restoration project called Seawilding. Initially unsure about these filter feeders in murky waters, he quickly came to understand their ecological importance—a realization that mirrored our own journey exploring the vital role of oysters as nature’s water cleaners in depleted shellfish reefs around the world.

At KMT, Marnik now oversees marine initiatives like the oyster nursery and seaweed farm, which he describes as a “living laboratory.” This setup serves not only KMT but also researchers and conservationists eager to study sustainable restoration and aquaculture methods. Though smaller than many Scottish estates, KMT is a biodiversity hotspot—a proof-of-concept venture designed to develop sustainable models that could inspire broader change across Scotland. Oyster restoration is really just the tip of the iceberg.

The idea is to reintroduce the native European flat oyster, a species decimated by centuries of overharvesting and environmental degradation. These native oysters play a critical role in ecosystem health, cleaning up to 240 liters of water per day while improving water quality and fostering habitats for other marine life. However, the restoration process is challenging no matter where in the world you are. European flat oysters take up to three years to mature, and even with careful management, mortality rates hover around 40-50%. Despite these obstacles, KMT has released over 50,000 oysters into the wild over the last three and a half years.

To prepare the oysters for life in the wild, KMT raises them in cages on a pontoon jutting out into Loch Melfort until they’re robust enough to survive without human intervention. These “trained” oysters are then placed in historically significant locations where oyster beds once thrived. By doing so, KMT aims not only to rebuild oyster populations but also to create three-dimensional habitats that support a wide range of marine species.

This project aligns with KMT’s commitment to long-term ecological impact, prioritizing biodiversity over “quick wins.” However, the team recognizes that scaling up oyster restoration across Scotland would require significant investments—potentially even establishing their own hatchery. And while we love to eat oysters, it’s important to note that the shellfish reefs that KMT is looking to establish go far beyond that, rebuilding an ecosystem that was once the marine backbone of Scotland.

Beyond oysters, KMT is exploring other innovative marine initiatives like kelp farming. In partnership with the Swiss nonprofit Open Climate Solutions (OCS), the two are investigating the potential of seaweed as a tool for sustainable agriculture and carbon sequestration. Seaweed-based fertilizers, for example, could help address global soil degradation caused by overuse, chemical inputs, and climate-induced events like droughts and floods. Although seaweed farming in Scotland is still in its infancy and faces challenges in its scalability and competition for marine space, KMT and OCS is committed to sharing their findings with the global community, fostering collaboration in this emerging field.

As we spent more time on the estate, the concept of the living laboratory truly came to life. KMT isn’t just advancing its own projects—it’s creating a collaborative platform for scientists, students, and technology experts from around the world to push the boundaries of our understanding of the natural world. The estate has become a hub for interdisciplinary research and innovation, forging partnerships that amplify its impact both locally and globally. During our visit, we were fortunate to overlap with one of their collaborators, Tritonia Scientific, a cutting-edge team specializing in advanced photogrammetry and marine mapping. Their work perfectly embodies the blend of technology and conservation at the heart of KMT’s mission.

Using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and cutting-edge software, Tritonia helps survey critical seabed habitats all around Scotland, targeting features like skate egg-laying sites, seagrass beds, and maerl coral beds. This data is then shared with government agencies like NatureScot to shape marine protection policies and guide sustainable development, such as fish farm placement and offshore wind energy projects. The technology allows for live-streamed data collection as well, which we were lucky enough to experience first hand during our team out to sea with the Tritonia team. It ultimately enables researchers in remote locations to collaborate in real-time, making it a powerful tool for global marine conservation, enabling the team based at their headquarters to see what we were doing in real time on Loch Melfort.

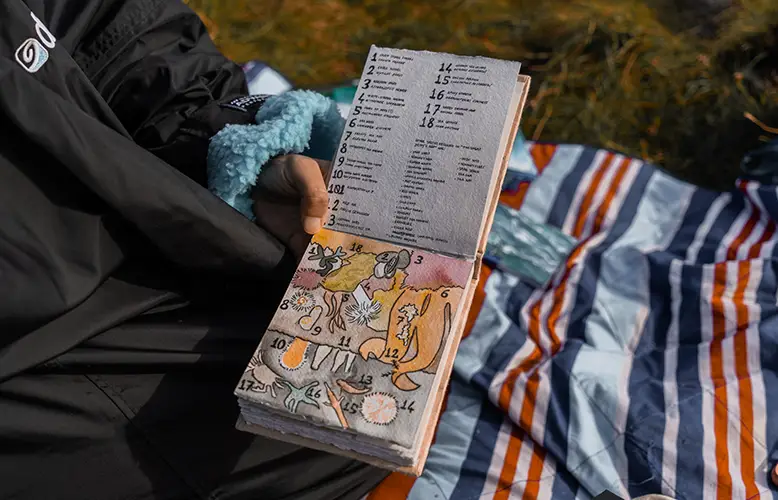

While onsite, we also experienced KMT’s collaboration with Mission Blue’s Hope Spots program, where the estate hosts an annual art residency, a unique blend of environmental awareness with artistic expression. Artists across mediums such as illustration, sound design, watercolor, and etching, spend several days immersed in the landscapes and shallow waters of the Argyll Hope Spot—the only one of its kind in Scotland. Participants snorkel and freedive to source inspiration from the marine life and unique ecosystems here, and ultimately create works that capture the beauty and fragility of this special region. This residency helps those awarded into the program a deeper connection to the natural world but also broadens the reach of KMT’s mission, inspiring audiences through the universal language of art.

Leaving KMT and heading back on the road to Edinburgh, it was hard not to feel a sense of serendipity. We’d experienced Scotland at its finest: sunlit days, calm seas, and an up-close look at KMT’s marine projects in full swing. Just days later, the region was battered by some of the worst storms and flooding in years, as if the Atlantic were reclaiming its turf. Someday, when the waters settle and KMT’s oyster beds are thriving, we hope to return and see Scotland transformed. Perhaps then, we’ll savor the fruits of their labor: native oysters, sustainably restored and served straight from the waters rewriting Scotland’s ecological future. Until that day, the taste remains a dream worth imagining.